June 5, 1963, Baltimore Maryland –There was no room on the bench when Mantle emerged from the tunnel for the second game of the first “crucial series” of the season. The dugout was crowded with writers and players waiting out a rain delay. You’d think one of you writers would get up and let a $100,000 ballplayer sit down,” one Yankee said, noting the breach of dugout etiquette.

In the top of the sixth, Mantle doubled and scored when Roger Maris hit a home run to give the Yankees a 3–2 lead. When, in the bottom of the inning, Mantle set off after a high fly ball hit to deep center field by Brooks Robinson, he was trying to keep the Yankees ahead in the game and put them back in first place, wrested away by the Orioles the night before.

“Mantle turned and raced back for it, running at full speed in his choppy, high-stepping sprinter’s stride,” Robert Creamer wrote in Sports Illustrated. “He looked up over his right shoulder as he ran, and as he neared the ball he lifted his glove to catch it. But the point of juxtaposition of glove and ball that Mantle had anticipated was theoretical—it lay a few feet beyond the seven-foot-high wire fence bounding the outfield . . . as the ball went over for a home run Mantle ran into the fence. His left foot hit on the downward stroke of its stride, and his spikes caught in the wire mesh. The front part of his foot was bent violently up and back.”

The Orioles knew all too well the perils of the unmoored chain-link, which was exacerbated by the absence of a cinder warning track. They understood immediately what had happened. “The bottom of it caved in,” said first baseman Boog Powell. “His leg went under and sprung back.”

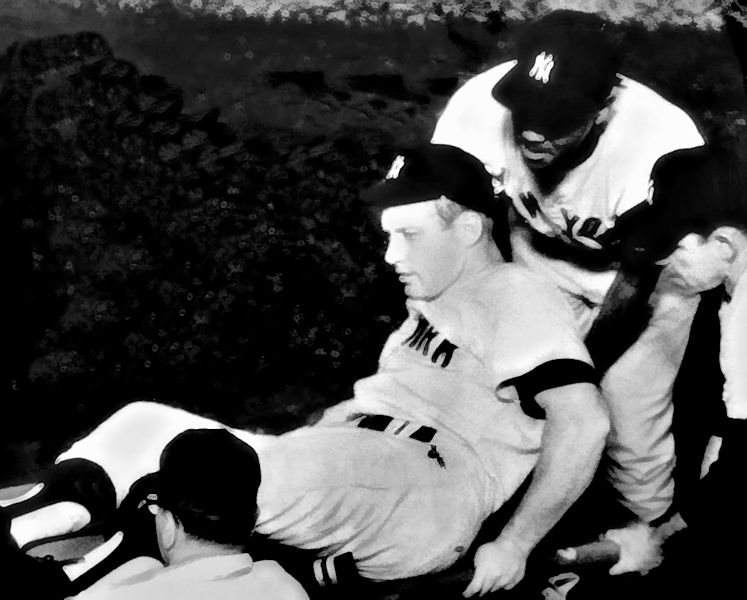

Mantle was surrounded by Yankees before Robinson rounded second base. “It’s broke,” he said. “I know it’s broke.”

This time he couldn’t refuse a stretcher. He was carried off the field looking like a “warrior on his shield,” one reporter wrote, and taken by ambulance to the hospital, where an X-ray detected an undisplaced, slightly oblique fracture of the third metatarsal neck, which means he broke one of the long bones in the foot that attach to the toes. His leg was placed in a cast up to his knee, and he was back at Memorial Stadium in time to hear the crowd cheer when the public address announcer confirmed the fracture.

“Isn’t there some way they can strap this thing up so I can play?” he asked when trainer Joe Soares predicted, accurately, that he would miss at least six weeks.

Dan Topping dispatched his twin-engine Grumman Mallard from Southampton, where he had been fishing the waters off Long Island. Reporters met Mantle on the tarmac at LaGuardia Airport and watched as he was helped off the plane. A photograph taken as he hobbled toward a waiting limousine was converted into an annotated medical chart with dates and arrows fixed to every part of his body except the grimace on his face: knees, tonsils, shoulders, rib cage; abscessed hip, fractured finger, fractured foot; pulled, sprained, and torn muscles; surgery, surgery, and more surgery.

In the limo, Milton Gross tried and failed to get Mantle to say he was unlucky, which furthered the apotheosis of The Mick. By the time the morning papers rolled off the presses, the “Man of Mishaps” had been transmogrified into “a tragic figure,” “the champion hard-luck guy,” and “the most fabulous invalid in the long history of sport.”

Team physician Sidney Gaynor removed the cast on June 24 and happily predicted a return by the All-Star Game on July 9. But on July 26, the cartilage in his left knee, torn in May 1962 and torn some more in the altercation with the cyclone fence, gave way. “It’s my fault,” Mantle said. “My foot hurts, so I have to run on the side of it. I think that’s what makes my knee bad.”

He had reached a breaking point: the cumulative injuries and mishaps, the residue of (unacknowledged) bad luck and primitive sports medicine, rendered him a part-time, one-dimensional player. He would play only sixty-five regular-season games in 1963. Of those, five would become intrinsic to the mythology of The Mick. He soared, he crashed, he persevered, he indulged, and he looked bad.

- Posted on

- Sunday 26 September 2021

- Dimensions

- 747*600

- Visits

- 353

- Rating score

- no rate

- Rate this photo

0 comments