March 26, 1951 Bovard Field USC Los Angeles

From Jane Leavy’s book The Last Boy

On March 26, the Yankees were back in Los Angeles to play the Trojans at USC—their last West Coast game.

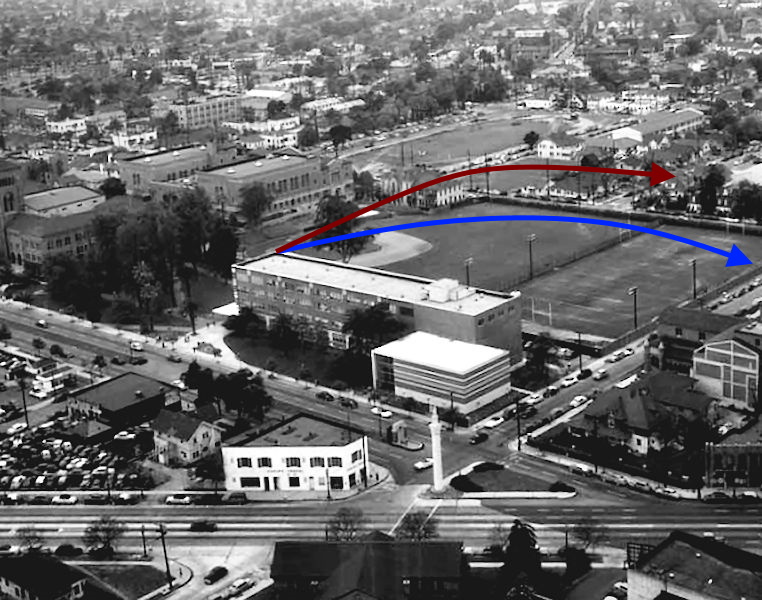

Cozy, palm-draped Bovard Field (318 feet down the right field line, 307 feet down the line in left) was tucked into a corner of the campus near the Physical Education building, which sat along the third base line. Beyond the right field fence lay a practice field where USC footballers were running spring drills.

The temperature at game time was only 59 degrees, with a wind from the southeast at 6 miles per hour. Conditions were Southern California dry—it hadn’t rained in twenty days. The National Weather Service noted “some haze.” Smog had not yet entered the vocabulary. Tom Lovrich, the Trojans’ ace, had already beaten the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Hollywood Stars that spring. A side-arming right-hander who threw a heavy, sinking fastball, he would go on to a respectable career in Triple A ball. When Mantle came to bat in the first inning, Lovrich didn’t even know that he was a switch-hitter. Dedeaux told him, “When in doubt, keep the ball low.”

The count, in Lovrich’s memory, went to two balls and two strikes. His intention was to throw the next pitch low and away, trying to entice Mantle to chase something off the plate, which he did. The pitch couldn’t have been more than eight inches off the ground. “Our catcher, John Burkhead, kind of dove or fell to his side to block a wild pitch,” Lovrich said. “Mantle actually stepped out of the box and reached across the plate. How he reached it, we never knew. You knew the ball was hit. It had that sound. A pitcher’s unfavorite sound.”

Dedeaux stood by the dugout, mouth agape. “You heard the swish before you heard the sound of the bat as the ball disappeared into the day.” Probably 550 feet +/- from home plate.

In a 1986 letter to baseball researcher Paul E. Susman, thanking him for his “unrelenting interest” in the matter, the Trojans’ center fielder Tom Riach described the play this way: “Riach ran just to the right of the 439 foot sign at the fence. I jumped up on the fence (approximately 8 feet) and watched the ball cross the practice football field and short-hop the fence on the north side of the football field.”

Another towering home run in the sixth landed on the porch of a house beyond the left field fence, 530 feet +/- from home plate. In the seventh, a bases-clearing triple flew to the deepest part of center field. In the ninth inning he beat out an infield single on a common ground ball, well played by the shortstop, who, pitcher Dave Cesca said, “would have thrown out any normal human being.”

“The greatest show in history,” Rod Dedeaux called it later.

Gil McDougald, on Mantle’s first homer, believes this was the longest ball he saw Mantle hit in their 10 seasons together with the Yankees. It was he says, “certainly further than the one he hit in Washington in 1953.” Tommy Heinrich says the ball “landed as far away from the fence as it was from the plate to the wall.”

Rod Dedeaux cites a football field that paralled the outfield fence running from the right field foul line to dead center field; Mantle’s ball left the baseball field near the 439-foot mark in right center, Dedeaux says, sailed over the football field (160 feet wide with sidelines of some 40 feet and hit a fence on one hop.

Dedeaux said “It was a super human feat.”

According to Bill Jenkinson, one of the country's most respected and trusted baseball historians and author of Baseball's Ultimate Power: Ranking The All-Time Greatest Distance Home Run Hitters, the drive to right field was about 550 feet, this from aerial photographs and indisputable. The drive to left field was no more than 500 feet, still truly amazing considering Mantle was only 19 years old throughout the 1951 season and stood about 5'11' and weighed around 185 pounds. But like other great sluggers, this set the stage for for distortion and exaggeration. Mantle fell well short of of hitting a 600 foot home run, on this occasion, as many have described. Still the fact remains, Mickey was just a teenager and had launched one of the longest drives in baseball history. It's a sobering reminder of how hard it is for anyone, including the strongest of batsmen, to launch a baseball 500 feet.

- Posted on

- Wednesday 18 August 2021

- Dimensions

- 762*600

- Visits

- 358

- Rating score

- no rate

- Rate this photo

0 comments